Ways to make your work more trauma-sensitive

The stresses of daily living, accidents, medical interventions, mental, emotional, and physical conflicts and violations, combined with cultural conditioning, and our early childhood experiences when our young nervous systems were most vulnerable, not to mention vicarious trauma, or trans-generational trauma, leave most of us disposed to experiencing trauma at one time or another.

Before we can attempt to talk about trauma, or discuss approaches for dealing with trauma, we need to define it, however due to its complexity and our unique and varied capacity to respond to trauma, it is difficult to define. Here is what Dr. Rober Scaer, author of The Trauma Spectrum says about defining trauma:

“I attempt to redefine trauma as a continuum of variably negative life events occurring over the lifespan, including events that may be accepted as ‘normal’ in the context of our daily experience because they are endorsed and perpetuated by our cultural institutions…. most of the population may be exposed to events that are actually traumatising but condoned by these institutions.”

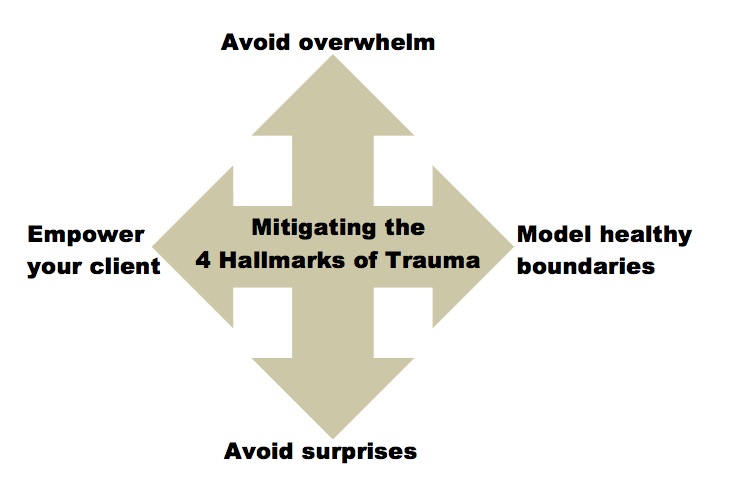

Four hallmarks of trauma

Working with people with trauma is complex, delicate work. Here are four common features of trauma or hallmarks of trauma that, as practitioners we can take into consideration to make our work more trauma-sensitive, and support our clients more.

Common features or hallmarks of trauma

- We were overwhelmed – such as when an event or events were beyond our range of tolerance or coping mechanisms

- The event was unexpected

- We felt helpless – we could do nothing about it

- A boundary violation occurred

How the four hallmarks of trauma can be used as a framework in our practice

Assuming we already know about building rapport with clients, confidentiality, non-judgment and unconditional positive regard for our clients, we can further refine our work to counter the effects of trauma by:

- Avoiding overwhelm

- Avoiding surprises

- Empowering our clients and giving them choice

- Setting and modeling healthy boundaries

How does this look in practice?

How does this look in practice?

It will be different for each of us, and here are some tips to help you think about using this framework in your practice, with your family, in your community … the ultimate goal is to create a climate of safety.

- To avoid surprises (and feeling overwhelmed) help your new clients prepare for their visit to you. Pictures are helpful. On your website or other communications, include a picture of you, your work space, the entrance, the parking space, etc. I also include pictures of people engaging with my horses, and an explanation of what to expect, how it works, etc. on my website.

Providing an information sheet on confirmation of appointments that includes extra information such as how to get to you, what to wear, what to bring, etc. can also minimise surprises and reduce overwhelm.

- To avoid overwhelm, go slow, and start small, until you get a sense of how much stimulus your client can tolerate. It’s ok to check in with them often for feedback on how they are managing – if it is not obvious.

- To help your client feel empowered, use invitational language, give them as much choice as possible, and ensure they don’t feel wrong by any choices they make.

- Set and model healthy boundaries. Simple things we might take for granted are being punctual and sticking to the agreed time, being reliable, consistent, congruent, and respecting their needs while taking care of our own.

Encourage clients to ask for what they need (to feel safe, comfortable), and explain that they have the right to say ‘no,’ and they have a right to their space. Acknowledge any time they set a boundary for themselves.

Hopefully these tips will stimulate your thinking about your practice and what more can you do to support your clients. Use your strategies outside your practice – with your children, friends, colleagues … remember we all have some trauma, and we can all appreciate the effort someone makes for us to feel safe.

To learn more about equine experiential learning and how to be trauma-sensitive, attend our CEEL facilitator training.